Boris Johnson recently announced that a UK inquiry into the government’s handling of COVID-19 will start in 2022 (with a parallel one planned in Scotland), and many more will emerge all over the world. But how should such inquiries be designed and run?

It’s highly likely that the most traditional models of inquiries will be adopted, just because that’s what people at the top are used to, or because they look politically expedient. But the pandemic prompted extraordinary innovation and there is no reason why inquiries should be devoid of any. The pandemic also affected every sector of life and was far more “systemic” than the kinds of issues or events addressed by typical inquiries in the past. That should be reflected in how lessons are learned.

So here are some initial thoughts on what the defaults look like, why they are likely to be inadequate, and what some alternatives might be.

A brief history of inquiries

There is a long tradition of inquiries after big public disasters or crises. In the UK, these have included: the Chilcot report into the Iraq War, the Hutton inquiry prompted by the death of Dr David Kelly, the Grenfell Tower inquiry, Lord Leveson’s inquiry on abuses by the media, and the Bloody Sunday inquiry.

There are also many other types of inquiry: parliamentary (one estimate suggests that there have already been around 60 COVID-related inquiries conducted by different select committees); royal commissions, audits that try to get to the truth; as well as internal civil service inquiries; and more localised inquiries, such as the one following the Mid-Staffordshire hospital deaths.

The UK political system is clearly fond of inquiries, and typically the first calls made by the media and opposition parties when something goes wrong is that there should be one. Some of these are governed by UK government legislation passed in 2005, which tried to standardise their formats, with a key aim to ensure that inquiries would be more trusted.

Yet inquiries continue to be denounced as “inside jobs” and “establishment stitch-ups”, and this will be a key challenge for any inquiry into COVID-19. The problem isn’t helped by the tendency of the government to appoint favourable people to run its own inquiries – which then usually conclude that no serious mistakes were made.

The standard inquiry model

Inquiries generally aim to find out: what happened, why, who’s to blame, and how to prevent it from happening again. Taking their models from the law and courtrooms, with witnesses, cross-examinations and written judgments, they happen in a physical place, and the aim is to establish the key facts, determine guilt, and then recommend new rules or laws to prevent a repeat of mistakes.

The default for any COVID inquiries will be very similar. As in the past, a leading establishment figure with a legal or governmental background will be put in charge. Written and oral evidence will be taken. A series of reports will be produced at some point in the future.

We can expect many groups to be nervous about the prospect of such an inquiry, and to wish to shape it to protect themselves: those politicians who made a series of misjudgments, particularly in the autumn of 2020; scientists whose advice at various points, particularly early on, may have been erroneous; officials whose machineries for crisis management were shown to be very uneven at best. Many people will be working hard to establish narratives and explanations to protect their reputations.

In general, governments will probably want pandemic inquiries that stretch as far as possible into the future. In contrast, opposition parties will probably want short, sharp inquiries with conclusions ahead of the next election. Neither may actually serve the public interest very well.

Hierarchical models and their limits

The traditional model of inquiry is a highly centralised, formalised and legalistic approach based on prose; a hierarchical exercise designed for hierarchies, apportioning blame to some of the people in charge.

This approach satisfies a deep human need for explanation and justice – if something has gone wrong, we want to see who is to blame and to see them shamed or punished. Westminster-style parliamentary systems are particularly keen on “sacrificial accountability”, while the US has its own style of often quite partisan inquiries.

But there are also serious limitations with this approach. It can cut against the kinds of honesty and self-awareness that are vital for learning. It can become a kind of theatre, encouraging performance rather than understanding.

It is less democratic both in practice and in spirit than the court system, which has juries to represent the public. It generates big incentives to distort or divert.

It’s also not a particularly good way to change how a complex system works or a way of giving people a chance to express their pain and grief, and to get answers from the powerful. This has been an important aspect of some inquiries – such as Grenfell – and is a vital part of post-conflict inquiries. Without the catharsis that comes from hearing testimonies from experience, it’s very hard to rebuild trust.

Whole-of-society approaches

There are many different options for inquiries ranging from “truth and reconciliation” inquiries, no-fault compensation processes and the ways industries such as airlines deal with crashes, to academic analyses of events like the 2007-08 financial crash. They can involve representative or random samples of the public (citizens’ assemblies and juries) or just experts and officials.

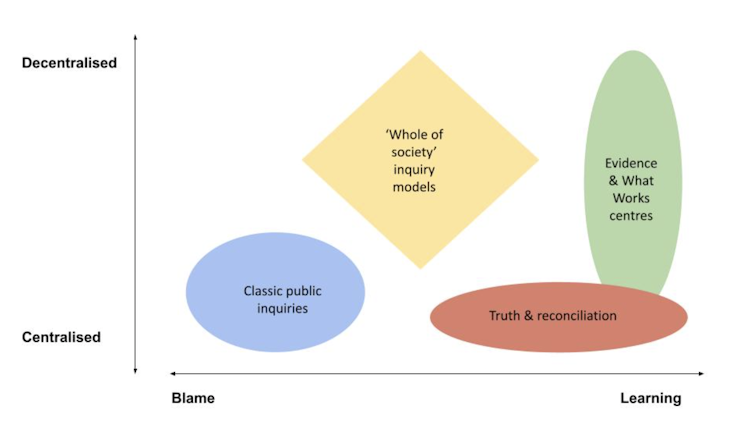

Author provided

Over the next few weeks at IPPO (the International Public Policy Observatory) we will be developing a more comprehensive taxonomy of inquiries with colleagues around the world and exploring pros and cons. How should they make sense of the many different levels of governance and decision making involved in COVID? Should they have distinct stages?

A crucial issue is to ask the right questions. Some should be basic questions of competence and process (what right and wrong decisions were made about lockdowns?). But the crisis has also thrown up many more fundamental issues: what have we learned about loneliness and isolation, how could we create better machineries for coordination between national and local government (the UK is particularly weak in this respect), or how should science advice be organised in the future, particularly to make more use of social sciences that were fairly marginal within Sage, which provides scientific and technical advice to support government decision makers during emergencies.

Alternative inquiry models could be more distributed and decentralised, creating spaces for many institutions to think about and absorb the important lessons. We could think of this as a “whole of society” approach to learning, to enable evidence-based deliberation on the issues and lessons that matter to many institutions and communities. For example, the lessons for schools are likely to be very different from those for the police, and they are most likely to be accepted by teachers if people they respect – including other teachers – are closely involved.

The COVID-19 crisis was uniquely wide-ranging and systemic. It needs a comparably systemic and inclusive model of inquiry. At the very least, let’s have a discussion. It’s highly likely the most traditional model will be adopted just because it’s what people at the top are used to. But that would be a huge wasted opportunity and would probably leave behind more distrust and suspicion rather than less.

You can read a longer version of this article on the International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO) website.

![]() Geoff Mulgan is co-investigator at the International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO)

Geoff Mulgan is co-investigator at the International Public Policy Observatory (IPPO)