On July 19 2021, nearly all legal restrictions aimed at limiting the spread of COVID-19 were removed in England. A requirement to isolate at the request of NHS Track and Trace remains for people exposed to an infected person and who aren’t double vaccinated, but other control measures such as the closure of nightclubs and limits on the size of indoor social gatherings have been lifted.

This move marked the end of the “roadmap” for gradually easing restrictions, which had been announced back in February. A major point stressed by politicians was that progress towards opening up again would be “irreversible”.

Yet following the relaxation of restrictions in the summer of 2020, control measures were ultimately reintroduced the following winter with national lockdowns in November 2020 and January 2021. So a natural question now is, will 2021 be any different?

Plateauing cases set to rise

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) infection survey gives an estimate of the number of people infected with COVID-19 at any point in time by testing a representative sample of the population. Its estimates of the proportion of people infected in England over the last year are shown in the graph below.

ONS Infection Survey

Infections have risen from low levels in April and May this year to a peak of around 1.57% in July, shortly after restrictions were lifted. The rate of overall infection then fell to 1.28% in August and subsequently plateaued.

The drop and levelling off may be due, in part, to the school summer holidays, as previously noted. The risk now is that infection rates could rise again from their already high levels due to a gradual increase in social contact, including through schools returning and possibly from more parents and other adults returning to workplaces.

Fewer cases leading to hospitalisation

However, a crucial factor affecting pressure on the healthcare system – which is what drives restrictions – is how common COVID-19 is in different age groups. According to the ONS, between July 10 and August 20 2021, the estimated rate of infection in the community was highest among 17- to 24-year-olds (3.23%). This is more than double what it was between January 9 2021 to February 19 (1.53%), when overall infections in England were at their highest.

In contrast, the rate of infection in the 70+ age group is just over half its January-February rate (0.38% in July-August, 0.72% in January-February). This difference is important, since younger age groups are at a lower risk of hospitalisation.

Combining data on hospital admissions by age and population estimates, both published by the ONS, we can see that in the week ending February 21 2021, the number of people under 25 admitted to hospital with COVID-19 was just 0.2% of the total number of people in this age bracket estimated to have had the disease over the previous week. In contrast, admissions of over-25s represented around 4.2% of the estimated cases in the community for this group. This shows how much stronger the link between infection and hospitalisation is as age increases.

Additionally, the risk of hospitalisation has fallen substantially for older people since vaccines have been widely rolled out. In the week ending August 22 2021, the number of over-25s admitted to hospital with COVID-19 represented only around 1.9% of the estimated number infected in this age group. So while rising infections in schools may translate to an increase in cases in older people, the impact on hospital admissions is likely to be lower than it would have been in pre-vaccine 2020.

Not on the road to lockdown?

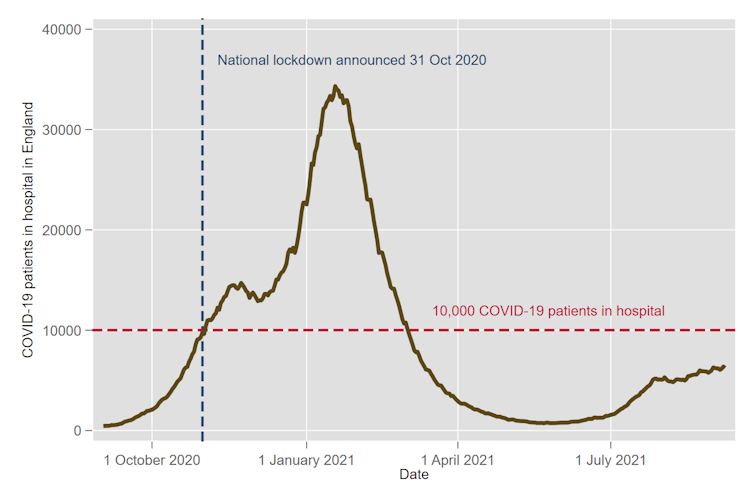

Throughout the pandemic, the need for restrictions has been driven by the number of patients in hospital with COVID-19. The graph below highlights the number of patients in hospital when the November 2020 lockdown was announced. At this point, on October 31 2020, the number of COVID-19 patients in hospital was just less than 10,000. Current patient numbers are over 6,000, having increased from less than 1,000 in May and June.

coronavirus.data.gov.uk

So can we think of the current situation as 60% on the way to lockdown? In some ways, yes. With around 10,000 patients in hospital with COVID-19, in October 2020 the pressure on the health system was judged severe enough to justify a national lockdown. However, the rate of upward trend is also key.

Two weeks after the start of this lockdown, numbers in hospital had reached just under 14,000 (restrictions take around two weeks to start bringing hospitalisations down). If we were to get to the same level in the coming months, it would likely be with a much slower upward trajectory than in 2020. While rising, the current rate of increase of hospital patients is not similar to the sort of rapid exponential growth seen just prior to previous lockdowns.

The critical difference between late summer 2020 and late summer 2021 is the successful rollout of the vaccination programme. Around 89% of people aged 16+ in England have received a first dose of vaccine and around 80% a second dose. The latest surveillance report by Public Health England indicates that against the dominant delta variant of COVID-19, two doses of a vaccine provide 79% protection against experiencing symptoms and, most critically, 96% protection against hospitalisation.

The same report indicates that from mid-July to mid-August, 97.5% of the entire English population had antibodies for COVID-19 either from previous infection or vaccination. This all suggests the vaccination programme has substantially weakened the link between cases and hospitalisation, not so much by preventing infection completely but protecting against hospitalisation in the vast majority of cases. One remaining uncertainty is to what extent protection offered by vaccines wanes. A booster programme to combat this is still to be finalised by the government.

The coming winter will inevitably bring more cases of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, and hospital numbers for COVID-19 are already high. However, mass vaccination has changed the prognosis. There is unlikely to be the same rapid increase in hospitalisations as seen previously. Some return of more minor restrictions in the winter is possible if hospital numbers continue to rise, but a full national lockdown remains unlikely.

![]()

James Gaughan and Peter Sivey receive funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).