Neil Lockhart/Shutterstock

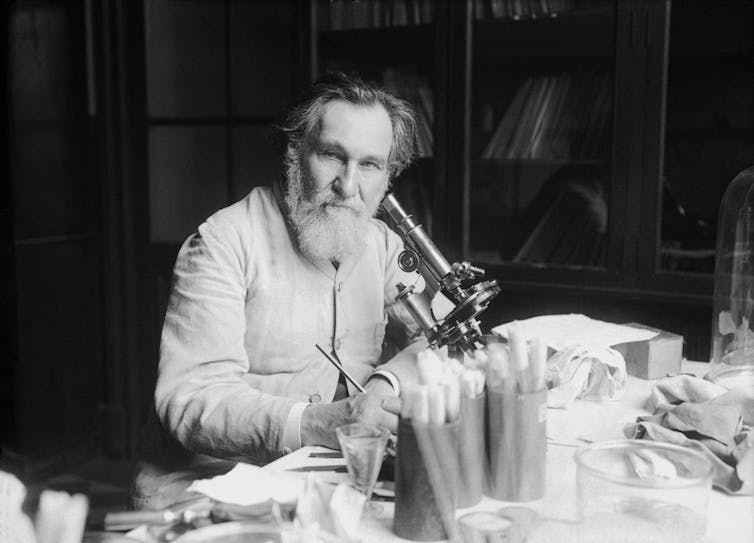

In 1895, on turning 50, Elie Metchnikoff became increasingly anxious about ageing. As a result, the Russian Nobel prize-winning scientist, and one of the founders of immunology, turned his attention away from immunology and towards gerontology – a term that he coined.

He was fascinated by the role that intestinal bacteria play in health and disease and suggested that people from parts of eastern Europe lived longer because they ate a lot of fermented foods containing lactic acid bacteria. Although popular at the time, this theory linking gut microbes to healthy ageing was largely ignored by scientists until relatively recently. We now recognise the importance that the trillions of bacteria, known as the gut microbiome, have in regulating health and disease.

Gallica Digital Library/Wikimedia Commons

Evidence has been accumulating for almost a decade that the microbiome composition changes with age. In 2012, research by my colleagues at University College Cork showed that diversity in the microbiome was linked to health outcomes in later life, including frailty. But we still didn’t know much about the effect of the microbiome on brain ageing.

In 2017, we revisited Metchnikoff’s ideas, putting them in the context of brain ageing, and showed that ageing induced changes in the microbiota and immune system, and was associated with cognitive decline and anxiety. However, this study, like many in the field, only showed an association between ageing and these factors. It did not prove that one thing caused the other.

In a subsequent study, we went a step further in showing that a microbiota-targeted diet enriched with the prebiotic inulin (a prebiotic feeds the beneficial bacteria in the gut) could lessen the effects of ageing in the brains of middle-aged mice. Yet it still wasn’t clear whether the microbiota itself caused the slowing of brain ageing.

In our latest study, we show that by taking the microbiome from young mice and transplanting them into old mice, many of the effects of ageing on learning and memory and immune impairments can be reversed. Using a maze, we showed that this faecal microbiota transplant from young to old mice led to the old mice finding a hidden platform faster.

The immune connection

Ageing is associated with an increase in inflammation across all systems in the body, including the brain. It is clear that immune processes play a key role in brain ageing, with a growing emphasis on the role of a specific immune cell, the microglia.

Ironically, these are the same class of cells that Metchnikoff visualised down the microscope, albeit in other tissues, in the late 1800s. We now also know that the activation of these cells is under constant regulation by the gut microbiome.

So the next part of the puzzle was to see if the negative effects of ageing on immunity are also reversible by transplanting the microbiota from young mice to old. Indeed, a lot of the inflammation was lessened.

Finally, we showed that chemicals in a region of the brain involved in learning and memory (the hippocampus) were more like that of young mice following the microbiota transplant. Our results show conclusively that the microbiome is important for a healthy brain in old age.

Was Metchnikoff’s step away from immunology premature in understanding the secrets of ageing? Indeed, the relative contribution of the immune changes seen in the mice receiving young microbiota to the overall rejuvenation effects deserves further study. But two big questions remain. What are the exact mechanisms at play? And can we translate these remarkable findings to humans?

Mice aren’t humans

Working with a controlled situation of mice – which have very defined genetics, diets and microbiome – is very different from looking at humans. We need to be careful to not over-interpret these findings. We are not advocating faecal transplants for people who want to rejuvenate their brain. Instead, these studies point towards a future where there will be a focus on microbiota-targeted dietary or bacteria-based treatments that will promote optimum gut health and immunity in order to keep the brain young and healthy. Such strategies will be a more palatable elixir indeed.

Metchnikoff’s overall tenets appear to be correct: protecting your gut microbes may be the secret to the fountain of youth. With advances in healthcare, longevity has markedly increased. And although we cannot stop the march of time, we can develop treatments that will protect our brains from deterioration and we have more than a gut feeling targeting the microbiome may be one such way. However, much work is still needed, though, to better understand how gut microbes are able to press rewind on some of the hallmarks of an ageing brain.

![]()

John Cryan receives funding from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) through the Irish Government’s National Development Plan (grants SFI/12/RC/2273 and SFI/12/RC/ 2273_P2) and through the Joint Programming Initiative: a healthy diet for a healthy life; investigating Nutrition and Cognitive Function (NutriCog) by SFI Grant ‘A Menu for Brain Responses Opposing Stress Induced Alternations in Cognition’ (AMBROSIAC) 15/JPHDHL/3270. He also receives funding from the Saks-Kavanaugh Foundation.

The author receives research funding, has been a consultant and been on the Speakers Bureau of food and pharmaceutical companies in the microbiome and neuroscience arena.