Illus Man/Shutterstock

The world has become interconnected at a level we never before imagined possible. States, banking, communications, transport, tech and international development organisations have all embraced digital identification. The current conversation hinges on the need to speed up registrations to ensure that every person on this planet has their own digital ID.

We have not stumbled into this new age of digital data management unwittingly. International organisations such as the World Bank and the UN have actively encouraged states to provide citizens with proof of their legal existence in an effort to combat structural poverty, statelessness and social exclusion.

To achieve this, social policy has deliberately targeted poor and vulnerable populations – including indigenous and Afro-descended people and women – to ensure they get an ID card to receive welfare payments. By aiming to include marginalised populations, they are targeting groups that historically have faced systematic exclusion and have been barred from formal recognition as citizens.

Lorena Espinoza Peña, Author provided

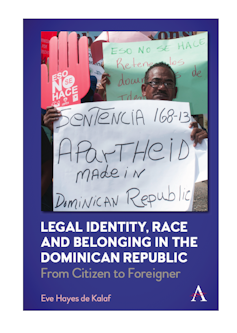

My research has revealed how states can weaponise internationally sponsored ID systems. The book that has come out of this work – Legal Identity, Race and Belonging in the Dominican Republic: From Citizen to Foreigner – highlights how, in parallel with World Bank programmes providing citizens with proof of their legal existence, the government introduced exclusionary mechanisms that systematically blocked black Haitian-descended populations from accessing and renewing their Dominican ID.

For years, people of Haitian ancestry born in the Dominican Republic have found themselves in a fierce battle to (re)obtain their ID. Officials claimed that for over 80 years they had erroneously provided people born to Haitian migrants with Dominican paperwork and now needed to rectify this mistake. These people say they are Dominican. They even have the paperwork to prove it. But the state doesn’t agree.

These practices culminated in a landmark ruling in 2013 that stripped Haitian-descended people born in the country of their Dominican nationality, rendering them stateless. In response, a fight-back campaign called for the civil registry to provide all people of Haitian descent with their state-issued ID documents as Dominicans.

In a damning critique of global identification practices, my research has revealed how international organisations at the time “looked the other way” as the state began weeding out and then deliberately blocking Haitian-descended people from accessing their documentation.

Who was deemed eligible for inclusion in the civil registry (meaning Dominican citizens) and who was excluded as foreigners (the Haitian-descended) was considered a sovereign issue for the state to address. As a result, tens of thousands of people found themselves without documentation and subsequently excluded from essential healthcare services, welfare and education.

Closing the global identity gap

We are seeing similar cases of this kind of exclusion erupting around world. In June 2021, I organised a conference at the University of London called (Re)Imagining Belonging in Latin America and Beyond: Access to Citizenship, Digital Identity and Rights. In collaboration with the Netherlands-based Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion, the event explored the connections between identity and belonging, digital ID and citizenship rights.

It included a paper on the French citzens caught up in BUMIDOM – known as France’s Windrush. We also heard about legal challenges brought by non-binary people in Peru, the experiences of non-domiciled Cubans rendered stateless, and the “anchor babies” debate over whether children born to undocumented migrants should be granted automatic access to US citizenship.

The event ended with an international roundtable that examined the use of digital ID registrations for discriminatory purposes in other parts of the world. This included discussions about vulnerable populations such as the people of Assam in India, the Rohingya in Myanmar and Somalis in Kenya.

Debates like these are only going to become more prevalent over the next 10 years: a homeless man who can no longer travel on public transport because the bus company only takes card, not cash payments; an elderly African American woman blocked from voting because she cannot provide a federal-issued ID; or a woman told she has to stop working because the system has flagged her up as an “illegal” immigrant.

For people who find themselves excluded from this new digital age, daily life isn’t just difficult, it is almost impossible.

And while the need to speed up digital ID registrations is pressing, in this post-pandemic world we need to take a step back and reflect. Calls for digital COVID passports, biometric ID cards and data-sharing track-and-trace systems are facilitating the policing not only of people crossing borders but also, increasingly, of the populations living within them.

It is high time we had a serious discussion about the potential pitfalls of digital ID systems and their far-reaching, life-altering impact.

![]()

Eve Hayes de Kalaf is an Executive Committee Member of the Haiti Support Group, a UK-based advocacy group.