The first death to be publicly attributed to coronavirus in the UK was of a woman in her seventies on March 5 2020. The same day, a spokesperson for the prime minister, Boris Johnson, warned the virus could spread in “a significant way” in the UK.

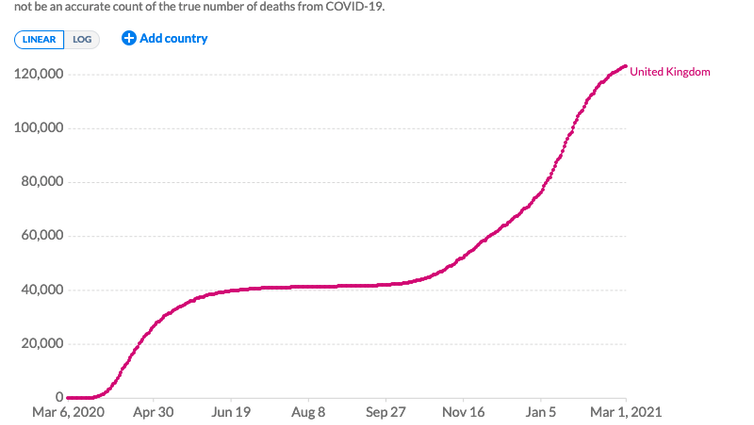

On March 16 2020, a group of 30 scientists concluded: “In an unmitigated epidemic, we would predict approximately 510,000 deaths.” At the time, this prediction was greeted with some incredulity. In hindsight, more than 120,000 deaths later, it appears less outlandish, although we will never know what would have happened in an unmitigated scenario because the UK did act to control the epidemic.

Internationally, mitigation measures have ranged from social distancing and isolating, to the most extreme of lockdowns. The debate about which measures of protection have been most effective, and which may cause more harm than good, has often been acrimonious.

Acrimony has often occurred when a relatively new disease arrives in the UK. As one of the founders of epidemiology, John Snow, said in 1853 during the middle of the 19th-century cholera epidemics:

The question of contagion in various diseases has often been discussed with a degree of acrimony that is unusual in medical or other scientific inquiries. The cause of the warmth of feeling that has been displayed has, in most cases, probably been unknown to the disputants. It is the great pecuniary interests involved in the question, on account of its connection with quarantine.

Looking back, we can now see that the pecuniary interests in 2020 were the interests of businesses that were shut down during lockdown, the interests of the government in maintaining an economy of the type they favoured, and the interests of the many individuals who personally suffered financially.

These individuals included 4 million people who lost income, but for various reasons were excluded from any of the government income support schemes. Since the beginning of the pandemic, some 1.8 million UK adults lost at least a third of their income with no resort to benefits or help of any kind. Many in this group now struggle to pay for food and everyday essentials – some will be starving.

We need to now start admitting and correcting some of the worst mistakes made. Too many people were unprotected not just from the disease, but also from the policies implemented to contain it.

Our World in Data, CC BY

Long-term consequences

A year on from the first officially recorded death with COVID-19, we know the current death toll, but we have little idea what the long-term health consequences will be.

However, some things are becoming more clear. One summary of the past year published in the BMJ is particularly damning. It explains that many of the policies that had been adopted in the UK – not least the closure of schools for the majority of children for so many months – has meant that, “This pandemic has seen an unprecedented intergenerational transfer of harm and costs from elderly socioeconomically privileged people to disadvantaged children.”

The protection of elderly people (in the way that we chose to do it) was also more effective in protecting those who are more affluent and was often done at the expense of poorer families, and their children, who were both far less protected from the disease and far more hurt financially.

Others may say that the countries of the UK had little option but to close schools for so long to try to control the disease. But the UK still reported the worst pandemic outcome of any large country in the world over a year on. Of all the countries with more than 12 million people, the UK had the highest crude pandemic mortality rate by the start of March 2021: 18 people had died of the disease for every 10,000 alive at the start of the year.

Why was the UK death toll so high? Ironically, it might have been much higher had austerity not stalled improvements to public health, which researchers have estimated led to 131,000 preventable deaths, again largely of the elderly, but between 2012 and 2019.

One reason the 2020 toll was still so high is that the disease was able to spread across the whole of the UK before it was widely realised it had. We now know that there had been many deaths within the UK attributable to the disease before March 2020 and that it had been spreading across the four countries of the UK for many weeks before that first recorded death. On January 30 2020, a man in his eighties in Kent died of COVID-19 exactly five weeks earlier than the woman in her seventies mentioned at the very start of this article.

A second possible reason as to why the death toll was so high is that the UK has become one of the most economically unequal countries in Europe by income.

Another early epidemiologist, William Budd, who was working alongside John Snow in the middle of the 19th century understood the role epidemics played in exacerbating inequality.

In 1849, Budd explained:

How important it is – even in regard to their own interests – for the Rich to attend to the physical wants of the Poor. To do this is one of our first and plainest duties. The duty itself we may evade, but we cannot evade the sure penalties of its neglect. By reason of our common humanity, we are all more nearly related here than we are apt to think. The members of the great human family are, in fact, bound together by a thousand secret ties, of whose existence the world in general little dreams. And he that was never yet connected with his poorer neighbour by deeds of Charity or Love, may one day find, when it is too late, that he is connected with him by a bond which may bring them both, at once, to a common grave.

Vaccines are being rolled out, deaths are falling, but enormous damage has been done. A year on we still do not have a good test, trace and isolate programme – at a time when many cannot afford to isolate.

The UK’s approach was not, in hindsight, the right response. Ranking so badly internationally tells us that. But it does not tell us the extent to which our prior circumstances were so bad in the UK that we were doomed to have a poor outcome – or to what degree we made an already bad situation worse.

![]()

Danny Dorling does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.