mundissima/Alamy Stock Photo, CC BY-NC

Facebook’s recent decision to block its Australian users from sharing or viewing news content has provoked a worldwide backlash and accusations of hubris and bullying. The row has also exposed the fragility of Facebook’s founding myth: that Mark Zuckerberg’s brainchild is a force for good, providing a public space for people to connect, converse and cooperate.

An inclusive public space in the good times, Facebook has yet again proved willing to eject and exclude in the bad times – as a private firm ultimately has the right to do. Facebook seems to be a bastion of free speech up to and until the moment its revenue is endangered. At that point, as in the case of the Australian news ban, it defaults to a private space.

My recent paper explores social media’s spatial hybridity, arguing that we must stop seeing companies like Facebook as public spaces and “platforms” for free speech. Equally, given their ubiquity and dominance, we shouldn’t see them solely as private spaces, either. Instead, these companies should be defined as “corpo-civic” spaces – a mixture of the two – and regulated as such: by internal guidelines as well as external laws.

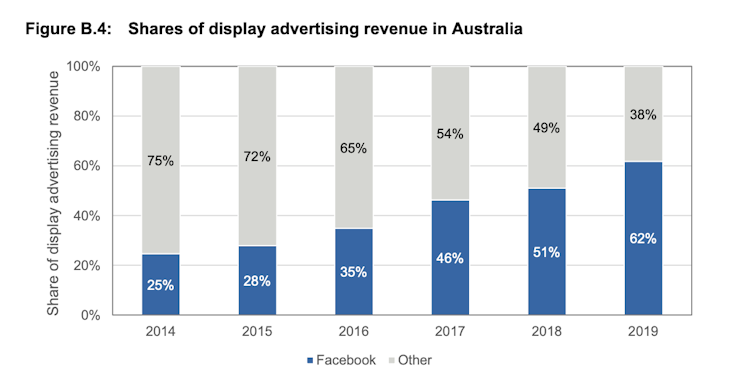

The recent Australian news block is part of a new set of laws developed in Australia to counter big tech’s monopoly power. The law in question responds to news companies’ complaints that they are losing advertising revenue to dominant content-sharing platforms such as Facebook. The law compels Facebook to agree a fee with news companies in an effort to reimburse them for the advertising revenue they lose to Facebook.

ACC Digital Platforms Services Inquiry: Interim report, September 2020

After lengthy negotiations during which Google threatened to withdraw from Australia, the company eventually chose to agree to those fees. Facebook didn’t follow suit. Instead, as if by the flick of a switch, the company turned off the news in Australia. Caught in the crossfire and also finding themselves blocked on Facebook were charities and government organisations, as well as Pacific communities outside of Australian jurisdiction.

The news block has played poorly for Facebook. Having claimed impotence in the face of growing disinformation for years, Facebook’s new-found iron fist has raised eyebrows. But this apparent inconsistency can be explained – though perhaps not justified – when we see Facebook as a public space with private interests.

estherpoon/Shutterstock

Social media firms aren’t the only organisations straddled between the private and the public. Shopping centres are a common example in the offline world. So are some apparently public spaces like New York’s Zuccotti Park where, in 2011, Occupy Wall Street protesters found themselves evicted both by police and by the park’s private owners, Brookfield Properties.

Social media platforms operate similarly. Just as a shopping centre relies on footfall, Facebook profits from active users on its platform. For Facebook, this profit is generated almost entirely via the revenue provided by online advertising.

It shouldn’t surprise us that, when confronted with the choice of whether or not to hand over some of that revenue to other companies, Facebook chose not to – even if that decision deprives Australian users of news content and a civic space to share and discuss it.

Nazis and nipples

The Australian news block is the latest example of a social media company falling short of its own principles. Governed by “community standards” that are effectively in-platform laws, platforms such as Facebook have a history of enforcing their rules on an ad-hoc basis. For years, researchers have argued that this system is inadequate, inconsistent and open to abuse.

Most glaring is social media’s inconsistent enforcement of its own community standards. Facebook and Instagram’s moderation has previously targeted women’s nipples and has forced sex workers offline, while self-professed Nazis were only forced from Facebook after their participation in the US Capitol riots on January 6 2021.

During the run-up to the US election in 2020, Mark Zuckerberg actually invited regulation from the government, which seemed to be an admission that Facebook had grown beyond its ability to regulate itself. Yet, as we’ve seen with events in Australia, the corporate half of these online civic spaces baulks at any external regulation that might be bad for business.

Corpo-civic spaces

So how should we regulate these hybrid spaces with competing and sometimes contradictory interests? My recent paper turns to “third space theory” for answers. Third space theory has been used to understand spatially ambiguous places, like when people’s homes become their workplaces, or when people feel a tension between their ancestral and adopted homes.

When applied to ambiguous spaces between the “corporate” and the “civic”, third space theory can help us better understand the unique regulatory challenges associated with social media companies. Facebook, for instance, is neither a wholly corporate nor a wholly civic space: it’s a corpo-civic one.

A corpo-civic governance approach would recognise that to heavily penalise and restrict social media companies would be to risk dismantling valuable civic spaces. At the same time, to see Facebook solely as a platform for free speech gives it licence to place maximising profits above ethics and human rights.

Instead, a corpo-civic governance model could apply international human rights standards to content moderation, putting the protection of people above the protection of profits. This is not dissimilar from the standards we expect of shopping centres, which may have their own private security policies but which must nevertheless abide by state law.

Because social media platforms are global and not local like shopping centres, it will be important for the laws that govern them to be transnational. Facebook may have blocked the news for Australians, but it wouldn’t make the same decision for hundreds of millions of users across several different countries.

Australia might be “Ground Zero” for laws aimed at reining in big tech, but it’s certainly not the only country drafting them. Having those state regulators work together on transnational policies will be crucial. In the meantime, events in Australia are a warning for tech companies and state regulators alike about social media’s hybrid nature, and the tension between people and profits that emerge from corpo-civic spaces.

![]()

Carolina Are does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.