What [do] I mean by sitting in a pit of fire? You’ve got every nerve ending that’s just going hellfire, and you just don’t know what to do with yourself.

Forty-two year old Emma has experienced chronic pain from a spinal cord injury for the last year. For Emma and many others, living with severe pain is now part and parcel of everyday life. It is estimated that 35-51% of people in the UK live with chronic pain. But communicating that experience can be a challenging endeavour.

We interviewed people with spinal cord injuries and women with endometriosis – a condition where tissue resembling the lining of the womb grows elsewhere in the body causing severe pain – in an effort to find out about their experiences and to learn more about how they talk about pain.

This research suggests that the inability to communicate pain effectively may partly account for delays in diagnosing some conditions. We also found that people with various types of chronic pain – such as that caused by endometriosis and spinal cord injury – often use metaphors to describe it.

Many speak of their pain in terms of being attacked. What might sound overly dramatic actually uses a variety of mechanisms, ranging from conveying high levels of pain severity and trying to make sense of the experience, to expressing the emotional consequences.

In using these expressions, sufferers may be trying to elicit support and empathy from others. At the moment though, widespread practice in pain consultation involves the use of numerical rating scales asking people to identify a number that best represents their pain.

The use of such potentially simplistic and reductionist tools means that a holistic assessment of the physical, psychological and social complexity of the pain experience is neglected.

Using metaphors to talk about pain

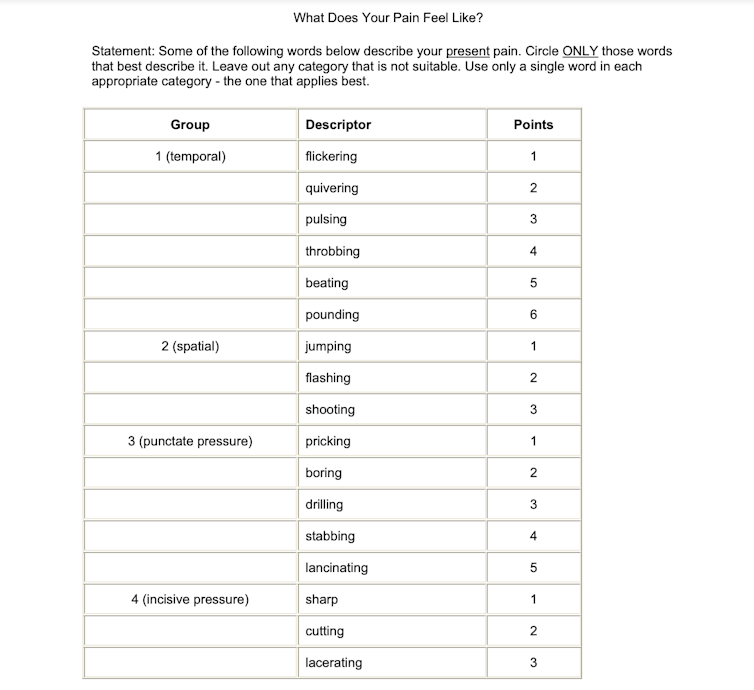

In conducting our research, we found that the ways people spontaneously talk about their experience of pain go beyond the measuring capacities of the standard assessment tools. For example, the McGill pain questionnaire asks people to rank each of the descriptive words such as “searing”, “pinching” and “flashing” in terms of their pain intensity.

Melzack/McGill University, Author provided

But many people describe their pain in ways that aren’t measured in this questionnaire. For example, one participant described their pain as feeling like “you’re dragging your organs”. Such creative and detailed descriptions often capture both the severity and the distress pain causes. However, not all expressions convey the intended message effectively.

Common pain descriptors such as “shooting” and “stabbing” pain may fail to articulate intended meaning as they have lost their metaphorical force due to overuse. These are known as dead metaphors. So more detailed creative descriptions, often involving similes, may be more effective in helping the listener to understand, assess and provide better support.

We found interesting examples of creative and extended metaphors such as:

It feels like somebody putting barbed wire through your belly button in a figure of eight … And then they set fire to the barbed wire and it starts getting hot and everything’s just being squished inside you.

Using highly personal and creative metaphors like this provides a mechanism to communicate pain in one’s own terms rather than being restricted by standardised assessments.

It’s like some little devil in the corner. Yeah, you know like that little exorcist thing in the corner … torturing me.

This language could help others understand more clearly how a sufferer is feeling and perhaps elicit some support. However, these benefits may come at a cost to the person in pain. We also found that some metaphorical expressions alluding to torture and attack could reflect individuals’ perceptions of pain as a physical threat, leading to higher levels of distress, fear and despair.

As a result, the use of such language could increase the attention that an individual pays to their pain. This has been shown to also lead to an increase in pain intensity, as people become more aware of, and sensitive to, the sensation.

Promoting effective pain talk

Pain is a private experience; encouraging people to find different and more appropriate ways to talk about it can help them make sense of their unique experience and describe it more effectively.

People with different conditions tend to use similar types of metaphorical expressions. For example, we found that words like “pins and needles” and “electricity” are often used to describe nerve pain associated with conditions like spinal cord injury. Similarly, expressions involving physical action such as “tearing” and “pulling” are more commonly found in descriptions of endometriosis pain.

This, in turn, can potentially guide doctors to identify potential causes of pain in certain conditions, like endometriosis. For example, a description such as “feeling like a balloon is about to explode” may point to inflammation, while “felt like I had tiny people with ropes tied tightly around my insides and pulling down” may be indicative of a deeper, more visceral pain.

Shutterstock

Pain is also an all-round experience, and its impact goes beyond the physical. The way that someone talks about their experience can also highlight its effect on other parts of their lives, such as mental health and socialising. For example, pain described as “all-consuming” could reveal an emotional dimension while talking about how people in pain “hide from the world” could indicate a drive to conceal pain from others and avoid seeking help.

Encouraging people to talk about pain in their own terms is key to understanding and supporting their individual needs. In fact, this is what our participants ask for: “Listen closely” or “Be more open-minded about the difficulty of describing pain I can’t explain well”.

Promoting creativity when it comes to talking about pain can empower those who feel their experience of pain cannot simply be captured or communicated by standardised measurements or numerical scales.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.