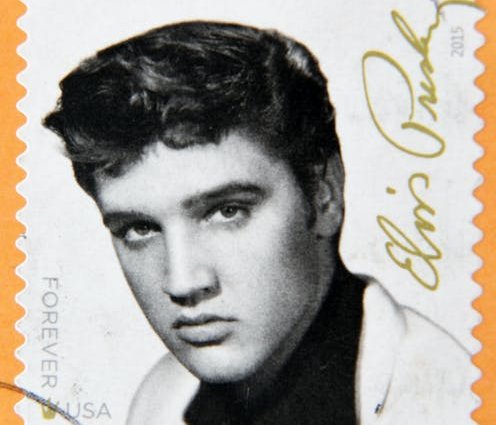

If you had tuned into the Ed Sullivan Show on October 28 1956, you would have witnessed an unexpected promoter of public health. Just before he took the stage to gyrate his way through his hit version of “Hound Dog”, the teenage heartthrob, Elvis Presley, received a polio vaccination live on television. The city’s health commissioner, there for the photo op, raved about Presley: “He is setting a fine example for the youth of the country.”

Indeed, young people were the problem. Polio was perceived as a disease of the child, not of the teenager. So when it was announced a year before Presley’s famous injection that the American virologist and medical researcher, Jonas Salk, had produced a vaccine that would stop the ravages of polio, initial distribution efforts were focused on infants and young children. Teenagers, however, were more difficult to convince.

Presley’s on-air vaccination was meant to change all of this. If the king of rock and roll does it, they hoped a generation of teens would say, I will too!

As it turned out, there were many reasons teenagers – and others – came up with to defy their king and refuse vaccination. One of these was almost certainly the 1955 “Cutter incident”, in which improperly prepared doses of the vaccine produced at the Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley, California, reached the market containing live poliovirus.

The ensuing outbreak did not improve public confidence. Another was the logistics of receiving the vaccine: three injections, each $3-5 (around $30-50 per jab in today’s money), was quite a commitment, especially for a population many did not consider to be urgently in need of immunisation. Indeed, the real game-changer came from the teenagers themselves, who, particularly in an association called Teens Against Polio, organised campaigns and sponsored the very popular (footwear optional) dances known as “sock-hops” for which immunisation was the price of admission.

Minimal celebrity influence

Perhaps more important than any of these for us now, however, is that the relationship presumed between public personalities and their fans is not nearly as straightforward as it has sometimes seemed. Individuals, then and now, are capable of being told by a celebrity to do something and, for all sorts of reasons, decline to do it.

This was a fact not lost on those putting forward public health messages in the latter decades of the 20th century. Over time, celebrity endorsements of public health projects fell away in favour of subtler alternatives. One of these was the rise of medical educational entertainment, or “medutainment”. This involved the integration of public health messaging into narrative developments on popular medical television programmes.

Since then, the more personal first-hand accounts of celebrities such as Lena Dunham, who has publicly documented her persistent endometriosis, and Meghan Markle and Chrissy Teigen, who have helped to destigmatise miscarriage, have shifted the relationship between celebrities and their fans when it comes to health and disease.

All of this means we should view with some scepticism the recent proposition that “sensible celebrities” – who have done “sensible things” over the course of the pandemic – ought to be our public health point people in the quest to popularise the COVID-19 vaccine.

Anti-vax movements

Rather ironically, on the question of vaccination, celebrities have recently been far more visible in anti-vax movements. We should be thankful, then, that their capacity to influence vaccination uptake either way is as minimal as it probably always has been.

In 2011, researchers in the US found that while only 24% of those surveyed had faith in what celebrities said about immunisation safety, over 70% had “a lot of trust” in their child’s doctor.

We know that vaccine hesitancy has often been about valid mistrust. That seems like a very good starting place to think about how to approach the COVID-19 vaccine.

This is not about how likeable or “sensible” the celebrity who urges us to do it is. It is about how much we can trust the various infrastructures and apparatuses that made that vaccine a reality in the first place: the public health experts who tell us to get vaccinated, the pharmaceutical companies who made and tested these vaccines, the medical practitioners who recommend it to us personally, the people who ultimately do the jabbing.

Do we have faith in this system? The goal here should not be about outsourcing likeability or faith to celebrities, but about focusing on repairing and maintaining goodwill between citizens and the state.

![]()

Caitjan Gainty is the recipient of funding from the Wellcome Trust for her 'Healthy Scepticism' project.

Agnes Arnold-Forster does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.