Anyone who’s ever worked in public service will understand the emotional toll it can take. In 1983, sociologist Arlie Hochshild coined the term “emotional labour” to capture this effect. She was talking about “the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display”. Emotional labour has been researched in a range of industries as diverse as restaurants, complaints agencies, and frontline emergency services. A new study of more than 500 elected councillors and MPs in the UK adds politicians to that list. It shows that emotional labour is a prominent feature of political work that can negatively impact politicians’ occupational wellbeing. It is also gendered. Women face more emotional demands in politics than men. These findings not only humanise an otherwise distant occupational group, but they also provide a snapshot of what it takes to be a politician.

To understand emotional labour as a psychological and behavioural phenomenon is, firstly, to understand the “emotion work” required of any employee to fulfil his or her job.

UK politicians surveyed in 2019 perceived emotional work as central to their occupational lives. For example, 60% believed that a critical dimension of their work relates to dealing with emotionally charged issues. And 71% believed that political work requires them to show many different emotions when interacting with people. To put this in context, only 55% of 911 emergency call dispatchers, child protection officers and prison correction officials in a similar study in the United States gave the same responses.

Note: this figure was created by Dr James Weinberg and is reproduced from the British Journal of Politics and International Relations under a CC-BY licence.

These findings reflect the fact that politics as a vocation focuses upon assisting, enabling or negotiating activities that revolve around the needs of other people. Whether it be in their constituency, political party or in a legislative setting, politicians must care, or at least appear to care, about others – and often complete strangers – in order to get their jobs done.

Playing nice

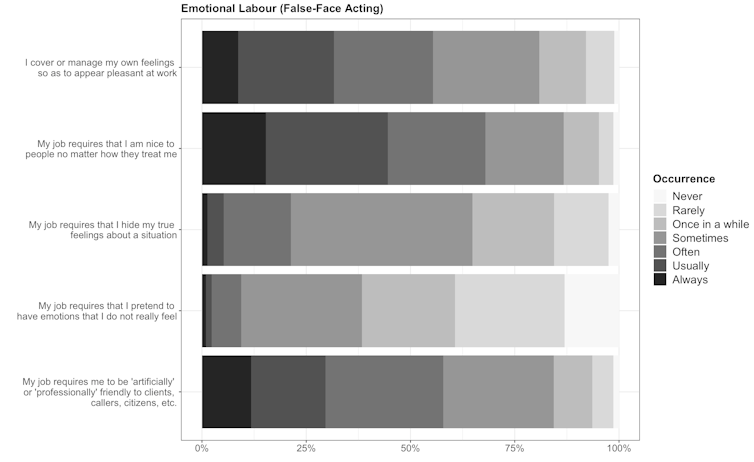

Emotional labour can involve what is known as “false-face acting”. This is when employees believe they must pretend to feel one emotion while actually feeling a different one (surface acting) or when they alter their affective state to internalise and feel a desired emotion (deep acting).

Note: this figure was created by Dr James Weinberg and is reproduced from the British Journal of Politics and International Relations under a CC-BY license.

UK politicians score highly for false-face acting. For example, 68% of participants felt they regularly had to be nice to people regardless of how they were treated by them. Faced with constant demands on their time and energy, and in a profession where people don’t shy away from saying what they think, it seems that politicians often feel like they have to manage other people’s emotions without expressing or showing their own.

Given that MPs and councillors are employed by an increasingly cynical public, it is possible – and arguably ironic given popular critiques of disingenuous politicians – that our elected representatives see false-face acting as a necessary feature of their public service. Put simply, emotional labour goes hand-in-hand with a political need to be all things to all people. As an occupational strategy, politicians may also be even more inclined than most frontline workers to engage in false-face acting because the personal costs of not doing (ie. electoral defeat) are uniquely ever-present.

A gendered experience

There are compelling reasons to think that emotion work may not fall evenly on all employees in an organisation. Previous studies of professions such as nursing have shown, for example, that men don’t feel the same emotional demands as their female colleagues or the same pressures to alter their own emotional displays.

Shutterstock

The same appears to be true for UK politicians. Women MPs and councillors self-reported higher levels of emotion work than men. In line with this finding, female politicians also self-reported spending more time helping others to feel better about themselves or calming clashes between other people (such as colleagues or constituents) in their working lives.

These findings reveal some of the unobservable inequalities that persist in British politics. In this instance, women are spending more time and effort managing other people’s emotions as well as dealing with emotionally charged situations. These gendered distributions of emotional labour highlight the ways in which informal practices and norms may disproportionately impact women and their experience of politics.

A health warning

Emotional labour is exhausting. It demands that employees suppress their own personal identity to accommodate others. It is not surprising, therefore, that false-face acting was associated with burnout among the politicians in this study. Symptoms such as negative self-evaluation, affective exhaustion, stress, occupational cynicism and generalised apathy were 51% higher among politicians who reported the highest levels of false-face acting by comparison to those who reported the lowest levels.

And whereas most service workers might seek peer support for the psychological pressures of their job, such choices are risky in the game of politics, where admitting vulnerability can be costly at the ballot box.

If we want politicians who are fit, healthy and able to make sensible decisions about how to govern effectively (both nationally and locally), then we must find ways to mitigate levels of emotional labour in political work and create relevant institutional mechanisms for supporting and training politicians in how to handle it.

![]()

James Weinberg receives funding from the Leverhulme Trust. He is affiliated with the University and College Union.