Eugene Lu/Shutterstock

There are now quite a few COVID-19 vaccines in the pipeline, but two seem to be making promising progress: the one designed by the US biotechnology company Moderna,

and the one developed by the University of Oxford in collaboration with AstraZeneca.

In both cases, the research teams have built on their previous experience with vaccines, adapting their existing models to meet the particular requirements of making a vaccine for COVID-19. This has led to the two vaccines being prepared using different approaches. Does that matter, and is one more likely to reach the goal of a safe, effective vaccine first?

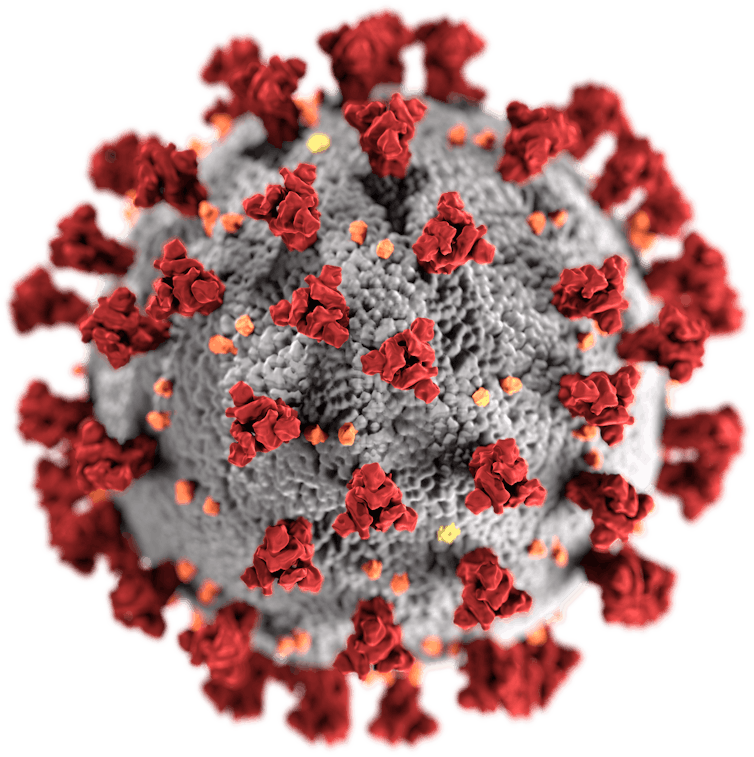

Although the way the body interacts with SARS-CoV-2 isn’t fully understood, there’s one particular part of the virus that we think triggers a protective immune response – the spike protein, which sticks up on the virus’s surface.

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Wikimedia Commons

So, the aim of the vaccine scientists has been to find a way to safely introduce that protein into the body in a form that stimulates an immune response. Both the Oxford and the Moderna teams have opted to do this using a piece of the virus’s genetic material.

Two types of special delivery

Viruses reproduce by infecting cells. Once inside a cell, the virus reveals its genetic material, which is like a set of instructions for making copies of the virus – which the cell then does.

For these vaccines, the researchers have selected just the bit of genetic material that signals how to make the spike protein. The rest of the code for the virus isn’t included, which should make the vaccine safer – it can’t lead to the cell reproducing the whole virus.

The Moderna vaccine places the blueprint for the spike protein in something called messenger RNA (mRNA). This is a molecule that the cell uses to deliver instructions when building proteins. The idea is to trick human cells into using this modified mRNA, so that they then make spike proteins just as they would substances for their own purposes.

The Oxford vaccine instead puts the code for the spike protein into the genetic information of a completely different virus that’s harmless to humans. When this altered (recombinant) virus (called ChAdOx1) infects human cells, the cell reads its genetic material and ends up making the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

In both cases, preliminary studies indicate that spike proteins get produced, and that this stimulates a robust immune response, including both antibodies and immune cells called T cells. It’s hoped that this combination will stop the actual coronavirus from using its spike proteins to latch onto cells and enter them. Both vaccines are being tested to confirm this happens.

Is there a better method?

This sounds good in theory, but in practice the use of viral genetic code is a very new way of making vaccines. The original form of the influenza vaccine, developed in the 1960s and still in widespread use, instead delivers the whole virus (which has been killed). It doesn’t grow inside the human cells, but the body can recognise and respond to it.

We know this works. Since we don’t know for sure which part of SARS-CoV-2 we should be concentrating on, perhaps using the whole dead virus and allowing the body to respond as it sees fit might be better?

US FDA/Wikimedia

The main problem with this approach is time. It takes six months to prepare a batch of influenza vaccine, because the virus has to be grown in the laboratory and then treated thoroughly to make sure it’s completely dead and safe to inject. We don’t want to wait that long to make a COVID-19 vaccine – particularly if it then doesn’t work. The European company Valneva is, however, using this approach. Its vaccine may turn out to be the best in the end, but it won’t be ready until at least mid-2021.

Another plan would be to make and deliver a preparation containing simply the whole spike protein, rather than asking the body to create it. This would be similar to the vaccines against hepatitis B and shingles, which are known as subunit vaccines. This should also be safe, and if it turned out that the protein wasn’t the correct target, it ought to be relatively easy to change.

The drawback is this type of vaccine requires repeat doses within a few months of each other, to ensure the body really does react to it. This is because the protein doesn’t last in the body. For instance, the hepatitis B vaccine needs three doses over six months to be effective, and many people require a booster within five years. If the initial course of a COVID-19 subunit vaccine was two doses, six months apart, that could be quite difficult to achieve for everyone in the world.

Recombinant vs mRNA – which is best?

While a number of mRNA vaccines have been produced against cancers and infectious agents, so far none are in routine use. There are some recombinant vaccines on the market already – for example ones for human papillomavirus (HPV) – so that technology is a bit further advanced. However, so far there is no real indication that one approach will be better than the others.

Anyway, it’s probably a good idea to try to make more than one type. It might be that one works better in a particular group, such as older people or children, since their immune systems are a bit different. Also, we will need to reach everyone in the world, so we will need a lot of vaccine. Having a few options could help us roll out some level of protection to all people in every country as soon as possible.

![]()

Sarah Pitt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.