Pexels

Men have long been recognised as being most at risk of suicide, but the Office for National Statistics recently reported the highest annual rate of female suicides in the UK since 2004.

This increase in female self-inflicted deaths comes at the same time as concerns the pandemic may increase the number of people who attempt to take their own lives. It will be some time before accurate UK data on suicides during lockdown is available, but in obeying the instruction to stay home, some people may have been deprived of the opportunity for intervention.

Studies already show that the pandemic is having a profound effect on many people’s mental health. Ongoing research from the University of Essex indicates this has particularly been the case for women, whose mental wellbeing has declined by twice as much as men’s during this time.

Having less social contact was shown to have the strongest influence on women’s wellbeing – more so than caring and family responsibilities or work and financial pressures.

Isolation and loneliness

Loneliness is already a recognised public health concern and can increase suicide risk for those with and without mental health disorders.

Here too, women may be more vulnerable to the impact of loneliness. Yet female suicidal distress is often not taken seriously or worse, dismissed as “attention-seeking” or manipulation when help is sought. This attitude can even come from healthcare professionals.

Pexels

Suicide and self-harm are deeply complex issues and dismissing the distress these acts signal can be a deadly mistake.

Women are more likely than men to make multiple suicide attempts, but this does not mean the attempts are not serious. This is because the chances of a fatal outcome increase with more unsuccessful attempts – so it’s essential that intervention is possible.

Police intervention

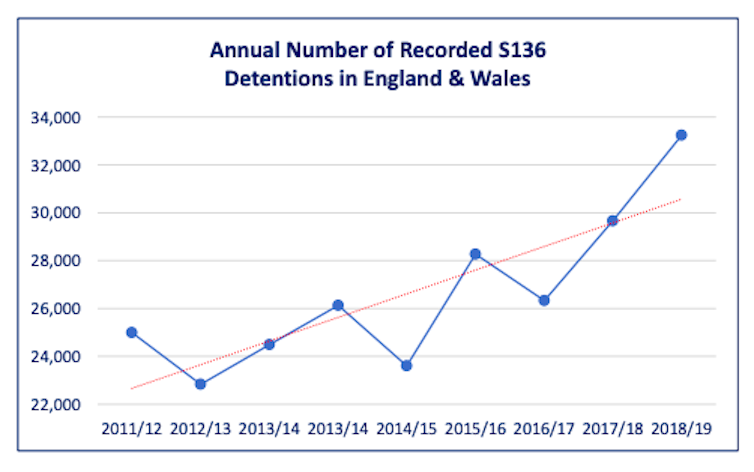

When someone appears to be experiencing extreme distress in a public place, the police have powers under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act to intervene and have the person removed to a place of safety. Involving the police in this way should be a last resort to keep people safe, but last year there were more than 33,000 such detentions in England and Wales – the highest number ever recorded.

As the red line on the graph shows, use of Section 136 is increasing despite efforts to disrupt this trend.

Author provided

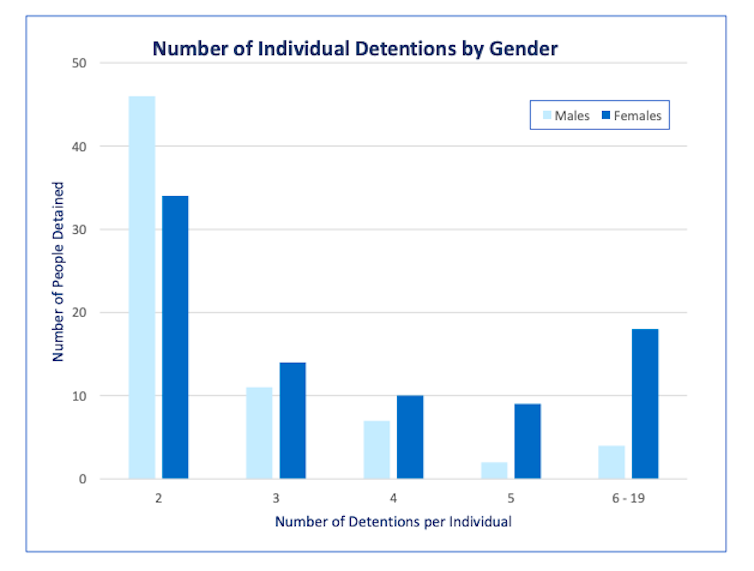

Nationally, as with suicide rates, more males than females are subject to Section 136 overall –55% in 2018-2019. But my research has explored repeated Section 136 detentions and found that more women are being detained multiple times.

I examined data from all repeat detentions in two neighbouring counties over a period of 28 months. In all, 155 people were detained 563 times. I found more males than females were subject to two or more detentions. But as the number of detentions per individual rose, the gender gap widened and it was almost exclusively females who were detained with the highest frequencies.

Author provided

Twenty-two people (18 women and four men) had the most detentions (203 in total). Each person in this group was detained between six and 19 times, sometimes more than once within a week. Overall, more than 90% of all the repeat detentions related to suicide or self-harm and repeats made up one-third of all Section 136 detentions in the two counties during this time.

Surviving short and long-term

As part of my research, I also interviewed six women who had histories of multiple suicide attempts and Mental Health Act detentions. I found that past traumatic experiences that had not been addressed had fractured their views of themselves and others. This had left them struggling to believe they had a future. As Kate said: “I have a total lack of hope.”

My study found that long-term, reliable support was the key to helping to ease the impact of trauma for some of these women. Yet in the short term, the responses of police and health care professionals also made differences. Heather said police officers had sometimes persuaded her away from a dangerous situation and to return to safety without having to be detained.

Amorn Suriyan/Shutterstock

Without alternative readily available suicide prevention measures in the community, Section 136 is critical to saving lives. Tragically, two of the women involved in my research, who had both survived numerous previous suicide attempts, have since died.

My colleagues and I are now examining data which suggests detentions fell in some areas during the initial lockdown period. Given then that varying COVID-19 restrictions look set to be with us for a considerable time to come – and the widespread impact on people’s mental wellbeing this may have – access to intervention and consistent support must be a priority. This is vital to prevent the next attempt from becoming fatal.

All names have been changed.

If you’ve been affected by anything in this article and don’t know who to turn to there are free helplines available to support you.

In the UK and Ireland – call Samaritans UK at 116 123.

In the US – call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or IMAlive at 1-800-784-2433.

In Australia – call Lifeline Australia at 13 11 14.

In other countries – visit IASP or Suicide.org to find a helpline in your country.

![]()

Claire Warrington currently receives funding from ESRC. This research was previously funded by Wellcome Trust.