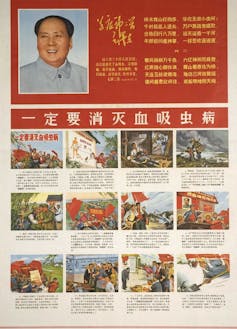

In early April, with much of the world under lockdown, China was already celebrating its purported victory in keeping the new coronavirus under control. In an effort to boost public morale, on April 2 the state-run Chinese Central Television, which acts as an ideological mouthpiece for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), re-aired a documentary about a Mao-era campaign against the disease schistosomiasis. The film, which was made in 2018, claimed the CCP’s leadership had successively eradicated the disease in China in the late 1950s, saving millions of lives.

Several blogs also recommended that people in Wuhan, the original epicentre of COVID-19, re-read Mao Zedong’s 1958 poem Sending off the plague God, which celebrated total eradication of schistosomiasis from Yujiang, a small county along the Yangtze in central China.

But contrary to China’s official claims that it had successfully eradicated schistosomiasis, this never occurred, a cover up I’ve investigated in a new book. By focusing on this ill-fated campaign in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, China revealed just how little the relationship between propaganda and public health has changed since the 1950s.

A ‘peasants’ disease

Also known as bilharzia or snail fever, schistosomiasis is a disease carried by a parasitic worm found in fresh water. It can stay in the body for years if not treated and be debilitating, causing organ failure leading to eventual death.

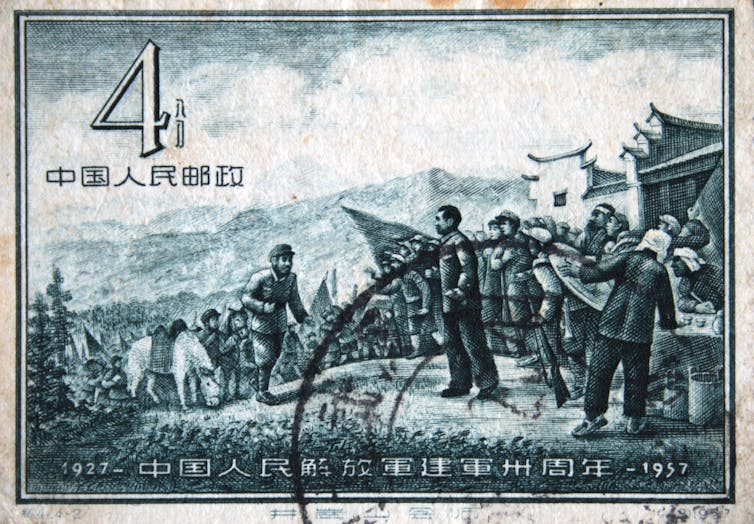

China’s anti-schistosomiasis campaign began in 1955 when Mao mounted a “socialist high tide” push to bring the socialist revolution to the Chinese countryside. The campaign was the centrepiece of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) focus on public health, which became the touchstone for public health innovation globally during the cold war.

The CCP leadership singled out schistosomiasis because it was a “peasants” disease which affected those working in the paddy fields and resulted from the traditional way of life of farming communities living in rice-growing regions.

National Library of Medicine

The goal was to eradicate schistosomiasis within seven years, by 1962. As schistosomiasis also afflicts people in many parts of the underdeveloped world, it was thought this would bring prestige to the country if the PRC could be the first to eradicate it.

My research drew on evidence from rarely seen party archives unearthed across eight impacted Chinese provinces and freshly collected oral testimonies from experts, local cadres and villagers who had participated in or were impacted by the campaign. I found that as soon as the campaign was set in motion, the authorities quickly learned that they really had little control over it.

In 1958, at the height of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, a utopian campaign to industrialise China, the PRC became the first country in the world to declare it had successfully eradicated the disease. But it hadn’t.

A grassroots health cadre from Jingzhou in Hubei province who was involved in the local implementation of the campaign told me:

We simply made up the figures. Officials from higher-ups knew it all along. To avoid getting into trouble or being sacked from office, they needed us to inflate or forge figures … It’s an open secret.

Damaging remedies

The CCP’s sense of urgency to control the disease, as with many other aspects involved in its centralisation policies, caused a fragmented and often contradictory local response.

With the advent of the Great Leap Forward in 1957 there was an even greater ideological demand to speed up eradication. Land reclamation and irrigation schemes were employed to bury and kill the snails – the vector that transmits the parasite. Such schemes not only proved extremely costly and wasteful, they also caused problems of water logging and water supply, contributing to severe flood and soil degradation that still haunts impact regions to this day.

In the end, the reclamation initiatives had to be abandoned. The subsequent switch to killing the snails using special pesticides further damaged the natural ecosystem, with long-lasting negative consequences on the environment.

This period of radical and rapid political change also saw people with the disease treated with higher doses of the toxic drug antimony tartrate, an internationally accepted intervention of the time known to control the infection in humans. Not only was this limited in its effectiveness, but my archival research shows the high doses of this toxic substance also claimed many lives.

SciePro/Shutterstock

Fiction versus reality

At the height of the Great Leap Forward, and in the aftermath of the subsequent famine, millions of new agricultural migrants and livestock were sent to the infected regions to help with agricultural production. Many were infected by schistosomiasis, while those who had been cured of the disease were reinfected. One report I found on local problems with the campaign said people protested that: “The leadership from higher up only cares about production, not human life.”

In the meantime, famine-related swelling, gynaecological problems and child malnutrition became even more widespread in the countryside. Unable to cope with the crisis, the PRC’s rural health system literally collapsed and ever more authoritarian and centralised methods came into play.

With increasing desperation, officials saw the promised goal of schistosomiasis eradication and the rural utopia it was to help create slipping away. Yet all this was quickly erased and forgotten. As well as Mao’s poem, a 1962 feature film called A Withered Tree Meets Spring immortalised the success of the campaign. These fictions were needed at the time to confront the brutal realities of the disease and the famine, and their devastating impact on people’s health.

Impelled to catch up with Yujiang – the first place to declare eradication in 1958 – 167 counties and municipalities hurried to declare near eradication in the following months. All turned out to be false, and there was a substantial cover up, as my study shows. Today, schistosomaisis remains endemic in many of these places, although it ceased to be a problem in some due to urbanisation, the subsequent depopulation of rural regions and the modernisation of agriculture.

China’s official narrative remains that the disease was eradicated but has returned – something it blames on political opponents who sabotaged the campaign. The latest official data shows 54,454 infections in 2016, with 69.4 million people at risk. In 2017, China’s National Health Commission issued new guidance which set the goal to control – not eradicate – the disease by 2020.

IgorGolovniov/Shutterstock

Uses of propaganda

In post-Mao China, mass media propaganda about the state’s success in improving people’s health concealed the reality of poor and mismanaged healthcare. In 2020, the same propaganda message has been used during the COVID-19 epidemic too.

In her seminal study on totalitarianism, the philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote that: “What convinces masses are not facts, and not even invented facts, but only the consistency of the system of which they are presumably part.”

China’s decision to air the documentary in April was a calculated one. By identifying with the victory narrative of the Maoist anti-schistosomiasis campaign, the otherwise hapless and frightened people in a totalitarian state could at least feel proud for being a member of a heroic nation that they believed was the first and only country to have eradicated schistosomiasis. By placing the struggle against COVID-19 within a victory narrative of improving health, the Chinese government continues to create a false sense of security and cohesion – one they require to ensure the stability needed to remain in power.

![]()

Some of the research referred to in this article was part of bigger project 'Between State and Community−Public Health Campaigns and Local Healing Practice in socialist Asia 1950- 1980: Mao’s China, a case study' funded by the European Commission Research Executive Agency (REA). Between September 2014 and December 2018, Xun Zhou was also in receipt of the Marie Curie Career Integration Grants (CIG) PCIG14-GA-2013-631344 from the REA.