Food insecurity has become a major issue in the UK. It is estimated that more than 200,000 children have had to skip meals during the coronavirus pandemic. The Trussell Trust has reported an 81% increase in the use of food banks compared to last year.

We are seeing the results of poor nutrition in children’s health. The number of children admitted to hospital with malnutrition in the first half of this year increased to almost 2,500 – twice as many as in the same period last year.

Our work, as a bioarchaeologist and a paediatrician, involves confronting the effects of poor nutrition on children in the past and those experiencing food insecurity in the present. The ghosts of the past can hold lessons for our present.

Lifelong consequences

Poor childhood diet can have lifelong consequences for health. It results not only in malnutrition but also a greater risk of cardiovascular and other chronic diseases. Children born into poverty have a lower life expectancy than their wealthier peers, and are likely to spend more of their life suffering ill health.

But it doesn’t stop there. This nutritional deprivation also affects the next generation. Low infant birth weight and high infant mortality are not just linked to the mother’s health during pregnancy: the mother’s own childhood circumstances are a factor, too.

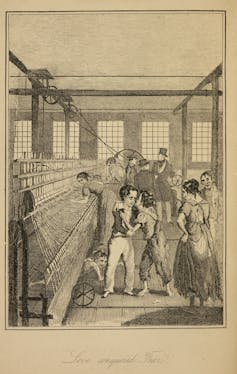

British Library

Poor health can therefore result from an accumulation of risk factors across generations, rather than a single lifetime. This becomes especially significant for families trapped in poverty and food insecurity. The odds can be stacked against a child even before they have drawn their first breath.

The stark effects of grinding, intergenerational poverty on children are clearly visible in the skeletons of working class children from 18th and 19th century England. Anthony Ashley Cooper, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury – who attempted to reform working hours – famously described children leaving the factory gates during the earlier part of the 19th century as:

A set of sad, dejected, cadaverous creatures […] the sight was most piteous, the deformities incredible. They seemed to me, such were their crooked shapes, like a mass of crooked alphabets.

Skeletal analysis of children from 19th century Leeds, Yorkshire showed a high number of severe cases of deficiency diseases such as rickets and scurvy, indicating severe malnutrition. This also caused severe growth stunting: for example, a 9-year-old girl and boy were the size of children half their age.

The bones were also very light and wafer-thin in cross-section. One of these children had sustained fractures to the ribs and jaw shortly before death, but such was the weakened state of their skeleton, these could have been caused even by very minor impacts. These nutritional deficiencies would also have led to a weakened immune system and ultimately their deaths.

Another site, Fewston in North Yorkshire, was home to a thriving textile mill during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Historical records show that children were taken from workhouses in the London parishes of Lambeth and Shoreditch to work in this factory in the North, far from any family connections they might have. Many of them perished. Their skeletons provide a biographical account of social injustice, which ravaged their bodies and led to their untimely deaths.

Child malnutrition today

Child malnutrition looks different in today’s Britain, and we do not suggest that levels of deficiency diseases and growth stunting today are as extreme as in the past. However, the steep rise in children admitted to hospital with malnutrition this year is cause for serious concern. Another stark warning is infant mortality, which saw an unprecedented rise in the UK between 2014 and 2017.

Whilst some children appear thin and undernourished, more so after school holidays when they don’t have access to school meals, others are overweight or obese – a result of cheap staple food high in saturated fats and sugars. Obesity in early life is linked to early onset type 2 diabetes in children, which has a profound impact on health and life expectancy.

RichartPhotos/Shutterstock

What both groups have in common is a lack of micronutrients such as vitamins and iron which are normally provided by a healthy, varied diet. Malnutrition at an early age has far reaching health consequences. Immune systems weakened from lack of nutrients are prone to more infections, which in turn lead to worse nutrition – a perfect vicious cycle.

Good and healthy nutrition is critical for cognitive functioning. It’s difficult for a child who is malnourished to concentrate in school and this contributes to lower achievement, trapping children within a never-ending feedback cycle of poverty.

Studies of the 18th and 19th centuries reveal how poverty can become embodied and imprinted upon the physiology of the poor from before birth. These inequalities were then exacerbated through deplorable living and working conditions. The physical effects of poverty and poor nutrition are being seen in children in the UK today.

![]()

Rebecca Gowland receives funding from The British Academy.

Christian Harkensee is volunteering as a Trust Board Member of Kitrinos Healthcare, a NGO providing medical care in refugee camps in Greece..