Nobody is more dangerous than he who imagines himself pure in heart, for his purity, by definition, is unassailable.

Author James Baldwin’s words, written in the America of the late 1950s, captures perfectly a feeling in the air that is currently troubling public discourse in many Western countries. Increasingly, questions once treated as complicated inquiries requiring scrutiny and nuance are being reduced to moral absolutes. Just look at Trumpism.

This follows a now dismally familiar pattern: two camps are identified, the acceptable “for” and the demonised “against”. The latter are cast beyond the pale, cancelled and trolled. Identity politics has become a secular religion and, like any strict sect, apostates are severely punished.

This can lead to a “purity spiral”, with the more extreme opinion the more rewarded in a pattern of increasing escalation. Nuance and debate are the casualties, and a kind of moral feeding frenzy results.

Are purity spirals inevitable? It is natural for humans to form “in” and “out” groups. Identifying a common enemy is often the key to group solidarity. Nationalist politicians and the marketing teams who serve them know how effective such strategies can be with ill-informed electorates. Equally, if an individual can manifest virtues valued by the group, this fosters a sense of self-worth and belonging.

Unsurprisingly, we have been here before. History demonstrates the ease with which ordinary people commit atrocious acts, particularly during crises. When you believe you are morally superior, when you dehumanise those you disagree with, you can justify almost anything. Take the example of one of the most consequential purity spirals, the Puritan Revolution in 17th-century England.

Word of God

The Puritans were certain that the godly majority supported them in toppling the tyranny of King Charles I. In their eyes, the monarch and his bishops were challenging the true word of God. The Puritans established an English Republic and Presbyterianism replaced Episcopalianism. Families were divided and fought during a bloody civil war across England, Scotland and Ireland.

The ultimate act of iconoclasm or cancellation is to kill another human being. The poet John Milton, in his Eikonoklastes (Icon Breaker) of October 1649, justified the execution of Charles I by arguing that shattering the sacred icon of monarchy had been essential to prevent the English people from being turned into slaves.

Living within a purity spiral defined Puritan society. Dress became simple. Luxury was forbidden. Christmas was cancelled. And discipline became a social watchword.

Marriage and patriarchy within the household were sacred. Children were given first names such as “Unless-Jesus-Christ-Had-Died-For-Thee-Thou-Hadst-Been-Damned”.

The “saints” competed to show their godliness. Those who did not accept the new culture were condemned. It was said of beggars, for example, that “the curse of God pursueth them” because they had abandoned family life. A new tyranny replaced the old.

British Museum

Looking back from the 18th-century, many feared new waves of Puritans seeking to enforce their moral codes upon an unwilling society, bringing public violence and political upheaval. It was natural for the historian Edward Gibbon to note during the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of June 1780 that “forty thousand Puritans such as they might be in the time of Cromwell have started out of their graves”.

Some philosophers, such as the Scot David Hume, argued that the Puritan purity spiral had been worth it. Hume likened the process to a wild storm bringing calm. He called the devout crusaders “fanatics”, and also ridiculous. He also asserted that their passion for liberty had made Britain a free state with limited monarchy and enhanced civil liberties.

Liberty, Equality, Fraternity

Should we encourage purity spirals because they are the source of our liberty? No, we should not. Take another purity spiral during the French Revolution – perhaps the greatest in history. Few events have so united a population.

British Museum

The Revolution began with the iconoclastic storming the Bastille, the prison symbolising absolutism whose walls were reduced to rubble. Within months, a new world was established. Aristocrats gave up their feudal rights. Empire and war were rejected. Liberty and rights were proclaimed. Hairstyles changed (no more wigs). So did fashion (no bling).

By January 1793, after years of controversy over the nature of liberty, the head of state, Louis XVI, was executed for treason. Monuments of monarchy then toppled. Royal tombs were desecrated. Many aristocrats changed their names to signal their dedication to republican revolution. The rich cousin of the king, Louis Philippe, duc d’Orléans, changed his name to Philippe Égalité.

But by the end of the year, the revolutionaries had turned upon themselves. A law passed the governing Convention on April 1, 1793 condemning any person deemed an enemy of liberty. Although Égalité voted for the law, he soon became its victim, guillotined in November by the Revolutionary Tribunal.

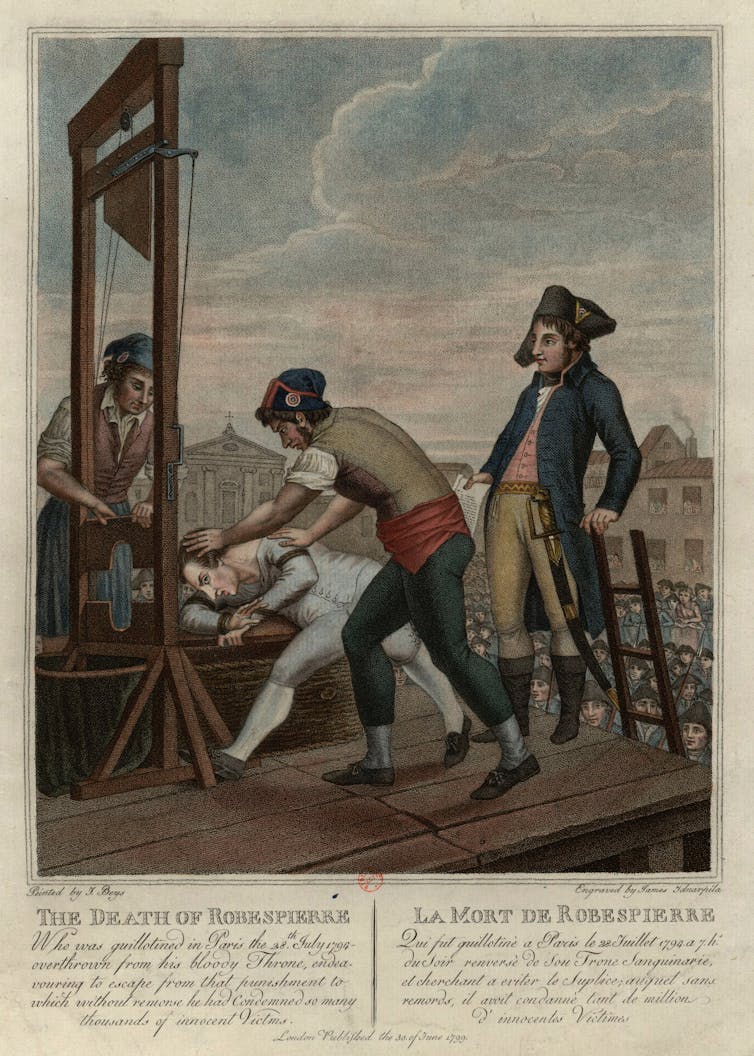

The republican church began to break up as virtue-signalling reached new heights. Under “the incorruptible” Robespierre, anyone with an aristocratic demeanour or critical of government was imprisoned. Thousands died. The philosopher Condorcet, a true supporter of equality between the sexes, was arrested for carrying a Latin book by Horace.

Having any connection to the English enemy brought suspicion. Thomas Paine remained imprisoned for almost a year because the US ambassador, Gouverneur Morris, who hated Paine, would not vouch that he was no longer English. Critics of Robespierre, such as Jacques-Pierre Brissot, ended up singing republican songs on their way to the guillotine, convinced that mad anarchists had hijacked the Revolution and commenced indiscriminate murder.

Bibliothèque nationale de France

Hume was right that fanaticism and virtue-signalling burn themselves out. Robespierre found himself on the execution block. The price was civil war. The Revolution then went the way of so many democratic revolutions, descending into aristocratic rule (The Directory) until a general conducted a coup. Napoleon Bonaparte crowned himself emperor, delighting the populace by combining public order and military victory.

In asserting his authority, Bonaparte warned that the alternative to his rule was a descent into Terror. He overran most of Europe, replacing monarchs with members of his family. His new aristocracy was the Légion d’honneur. Savvy followers learned the lesson, including Stalin and Mao – make the people afraid of so-called fanatics and they will follow you.

Lessons for today

The lesson: purity spirals can topple authoritarian regimes, but assist new authoritarians in ruining the lives of innocent people. They turn families and friends against one another.

At the end of his life, Hume worried that a lust for liberty was turning fanatical. Hume’s disciples attacked the French Revolution for reigniting religious warfare. Instead of killing each other to save souls, people now did so in the name of freedom. Civil liberties were forgotten.

As polarisation intensifies, people are increasingly loath to consider opinions that don’t reinforce their own. Quite literally the road to hell can be paved with good intentions.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.